Turning the Camera in Layers of Fear

Does not contain spoilers for Layers of Fear (2016), Layers of Fear 2 (2019) or Layers of Fear [Remake] (2023)

Contains light spoilers for: Rings of Power Season: 2 Episode 7

Silent Hill 2 Remake by Bloober Team was received fairly positively. I love the horror genre and Silent Hill—especially so—so I grabbed a copy of Silent Hill 2 for my PS5... and then proceeded to download the Layers of Fear Remake from PSN. Yeah, I decided to be thorough. I was curious about the game that first put Bloober Team on the map of horror game studios.

I hadn’t played any of their titles before, largely due to their middling reviews. It also doesn’t help that Jacek Zieba, the director of their upcoming game Cronos, said, “Okay, we made some shitty games before, but we [can] evolve.” That sentence left a bit of a sour taste in my mouth. I get what he meant, but I think it’s important to appreciate your own work and recognize how much it helped you grow. Without those “shitty games,” you wouldn’t be where you are today.

I don’t believe in shitty art per se. I think there are well- and poorly-executed ideas mediated through art.

Layers of Fear is a poorly executed idea—2/5 stars. Review done.

The remake combines Bloober Team’s first game, Layers of Fear, and its sequel, Layers of Fear 2, upgrading them visually with UE5 technology. Unfortunately, narrative and character development are not its strongest points. The experience feels like your average Blumhouse haunted house horror movie—occasionally obtuse and overly poetic in its attempt to explore the struggles of creating art and the sacrifices it demands. It’s as if the game is "faking" the depth of its characters through highfalutin expressions rather than genuine storytelling.

I could dive deeper into the unsuccessful attempts at narrative threads and the overuse of Goya’s paintings in Layers of Fear, but I’ve found it’s not worth exploring. Instead, I want to focus on something far more interesting: the game’s main mechanic of rearranging the environment.

This mechanic is a fascinating approach to evoking fear. Let’s explore that instead.

Layers of Fear is a first-person video game. The core gameplay revolves around exploring an old mansion where the internal layout keeps changing as you progress. These changes are primarily achieved by rearranging the order of connected rooms and altering the room decorations.

What’s crucial to note is that [almost] none of these changes happen in view. Instead, they occur when you’re not looking—either when you’re facing away or just before you enter a room. This subtle sleight of hand forms the backbone of the game’s fear mechanic. The idea that a completely different scene might appear when you turn the camera around is profoundly unsettling—and undeniably effective in creating tension.

I believe most readers are familiar with the concept of fearing what we cannot see—the fear of the unknown. Our animalistic instincts kick in to anticipate danger, and our brains construct narratives and expectations, conducting chemical processes to heighten alertness and caution—sometimes overly so.

This primal fear is one of the reasons why the first Alien movie works so well as a horror film. You don’t really see the Alien that often. It’s the not seeing the creature that builds tension. Sir Ridley Scott has said this was very much intentional, relying on the viewer to construct a more terrifying reality in their imagination than anything that could be shown on screen.

This concept is also the foundation of jump scares—the abrupt transition from not knowing or anticipating to brutal or horrifying knowledge. But we’re all aware that a horror movie cannot rely solely on jump scares. They lose their impact with overuse. Why? Perhaps because repetition robs them of mystery. Once the viewer expects to be startled, the moment ceases to evoke true horror and instead becomes a predictable jolt—an external, superficial reaction.

I’ve always liked the comparison of cheap jump scares to tickling: both aim to trigger a desired outcome (fear or laughter) without genuine substance. This is why a well-earned jump scare can be as satisfying as a well-crafted joke—it’s the quality of execution, not the mere presence of the tactic, that makes it resonate.

Personally, I’m very desensitized to horror movies. I love them, but they rarely leave me mortified. Yet, horror video games are a completely different story. I get so anxious while playing that I can’t muster more than two hours per session.

I understand why there’s such a difference between how I experience horror in movies versus video games. In a movie, I’m merely an observer. In a video game, I’m a participant—responsible for every action. What’s particularly terrifying for me is turning the camera around. The simple fact that I have to use the camera fills me with dread. My brain tells me that anything could be waiting there, lurking just beyond my sight, within the framework of the environment—and I must face it voluntarily.

This is why games like the Amnesia series and Silent Hill 2 work so effectively. They manipulate your perception by obstructing your vision—whether through darkness or fog—forcing you to constantly guess what might be ahead. All the while, they build tension masterfully, keeping you uncertain of when—or if—that tension will collapse. This perpetual unease is what makes these games so gripping and uniquely horrifying.

Layers of Fear attempts to exploit this concept to a higher degree, though somewhat unsuccessfully. Frequently, when you rotate the camera, the scene behind you is completely altered—a different room, a new hallway, unfamiliar decorations, or an entirely reimagined space. Because the game manipulates the environment so drastically, your brain can’t even form expectations. The framework of what’s possible expands, and with it, the scope of the unknown. This makes the simple act of turning around a gut-wrenching experience. It instills paranoia.

At least, it did for me—initially. But, much like jump scares, overuse dulls the impact. The repetition of this mechanic makes the unknowable a known quantity. Unfortunately, Layers of Fear leans so heavily on this technique that, after a while, I became desensitized. Patterns emerged. I recognized the same rooms, the same changes. The magic faded. The game’s carefully crafted illusion crumbled, and I saw the seams: models of rooms loaded and unloaded from memory.

By that point, I was sprinting through the game, rarely bothering to look back unless it was strictly necessary to progress. The fear gave way to routine.

Interestingly, the designers behind the game might agree with this critique. In its sequel, Layers of Fear 2—which is included in this remake—the use of environmental alterations is significantly reduced. These changes feel far more unpredictable and impactful. Unfortunately, even in the sequel, this effectiveness diminishes over time.

The concept of not knowing and the act of turning the camera are incredibly powerful tools. What’s fascinating is that they can operate even without the creator’s explicit intent. I experienced this firsthand when I accidentally played Gone Home (2013) as if it were a horror game.

I went in knowing nothing about the game—no trailers, no detailed reviews—just vague but glowing recommendations. Intrigued, I gave it a try. The game begins in a dimly lit house, where you explore room by room, uncovering the narrative through environmental storytelling.

Throughout the entirety of the game—even up until the very end—I moved cautiously through the house, turning around carefully at every corner. I was afraid. I didn’t know what to expect. The clues I uncovered triggered my heightened sense of caution, keeping me in a state of wary exploration.

Yet, in the end, there was nothing to fear. It was, in fact, a lovely queer story. I couldn’t help but chuckle at myself afterward. A few years later, I heard from someone else who had also accidentally played it as if it were a horror game, and it gave me a good laugh.

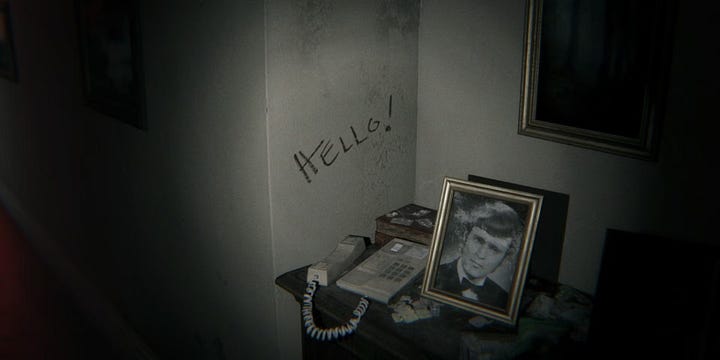

I think, to this day, the best video game—or rather, the best demo of an unmade video game—that employs this concept to perfection is P.T.. It always comes back to P.T., doesn’t it?

Silent Hills P.T. has become the stuff of legends. The unmade project by Hideo Kojima and Guillermo del Toro has inspired countless imitations and spawned an entire subgenre of atmospheric horror. Its influence is undeniable.

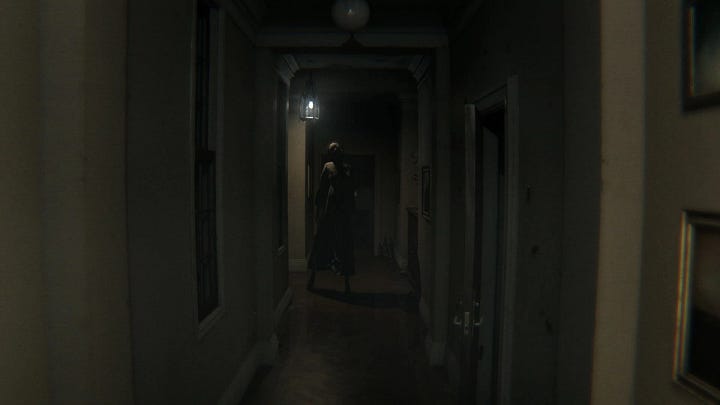

The core gameplay loop of P.T. involves endlessly moving through the doors of an L-shaped corridor until you solve the puzzle to escape. Each time you pass through, the corridor shifts—sometimes subtly, sometimes drastically. Occasionally, you’re confronted by the apparition of "Lisa," whose presence is utterly terrifying.

On paper, this sounds strikingly similar to the gameplay loop of Layers of Fear. Yet, while both games use the concept of an ever-changing environment, P.T. excels where Layers of Fear falters. There are many reasons why one succeeds while the other struggles, but here, I want to focus on a single aspect: why the concept of a changing room doesn’t lose its power in P.T.. Even as the expectation of a shifting corridor becomes a known quantity, it remains effective—it becomes the expectation itself.

The reason is quite simple, and I have to admit, there’s not too much to analyze here. While the changing corridor in P.T. becomes an expectation, the changes themselves remain unknowable and grounded within the limits of reason. These shifts aren’t random; they enhance the mood, sometimes serving as part of a puzzle. This careful balance is something Layers of Fear struggles to maintain.

In Layers of Fear, environmental changes often occur upon camera rotation without purpose. They seem to happen for the sake of it—perhaps because it looks “cool.” However, this tendency creates a new, unintended expectation for the player: a change for change’s sake, devoid of meaning. This lack of purpose introduces a different kind of limitless expectation. While limitless expectation might sound compelling, it’s less terrifying. When the scope of possible outcomes expands to include non-horrifying scenarios, my mind starts conjuring ideas beyond fear. These ideas might not entirely replace the horror scenarios, but they certainly dilute their impact.

On the other hand, P.T. carefully surprises you with each iteration of the corridor, but always within the boundaries of things designed to scare you. The changes are deliberate and meaningful, never overstaying their welcome. If those surprises become repetitive or reveal discernible patterns, the illusion falters. It becomes evident that even our imagination has limits—it’s finite. Similarly, if P.T. had introduced alterations without purpose, players would start to expect anything—horrifying or not—which diminishes the tension.

A fun technical note: the character "Lisa" is attached to the player’s camera from behind, meaning she’s always lurking just out of sight. This subtle design choice underscores the paranoia the game evokes.

Simply put, P.T. keeps its scares within a controlled scope, ensuring that every change serves a purpose. It doesn’t overstay its welcome, nor does it wander aimlessly. It’s this balance that makes it so effective.

Despite these shortcomings, I can see why Konami chose Bloober Team to handle Silent Hill 2. Much of their work explores subjective perspectives and how the world can be reshaped in real time, aligning well with the themes of Silent Hill. Now, perhaps, I’m ready to finally play Silent Hill 2 Remake.