Four Games That Changed My Brain Chemistry, Part 2: The Witness

Spoiler warning: This essay contains major spoilers for The Witness (2016)

The Witness

"Be knowingly open, empty, luminous presence of awareness" is the sentence that arises in my consciousness when I think of The Witness. I’ll return to this sentence later, but try to meditate on it while going through everything here. This video game has [indirectly] affected me in more than one way, and I will always be deeply grateful for it.

The Witness is a puzzle game that requires only a basic familiarity with the gaming platform of your choice - just interfacing with it. Nothing else is needed—no prior preconceptions, beliefs, or skills related to video games. You are inexplicably dropped onto a desolate island with no introduction, menus, text, UI, tutorial, soundtrack, guidance, or narrative, and you are expected to solve puzzles presented on flat panels scattered throughout the island. This might evoke comparisons to Myst and Riven, but I assure you, The Witness is a very different beast entirely, and I want to build my case for it step by step.

The game's main setting is an island with visually distinct regions, each representing a different area of interest. These range from a desert to a monastery, a tropical forest, a mountain, a lake, and so on—18 areas in total, which you are free to explore in nearly any order you choose. The art direction is deliberately stylized, a solid choice that helps the game withstand the passage of time rather than trying to compete in the race for realistic graphics which become outdated in few years.

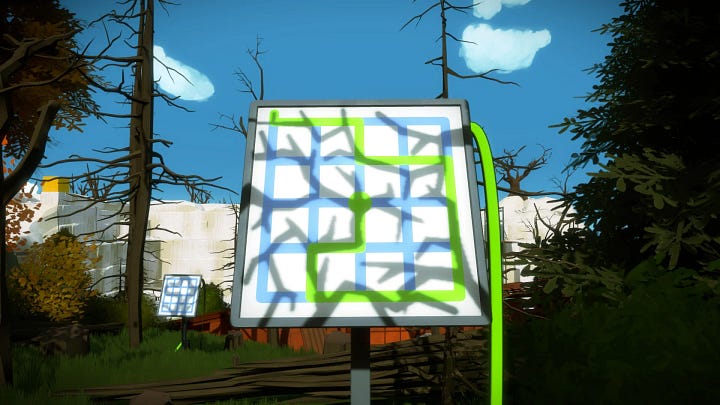

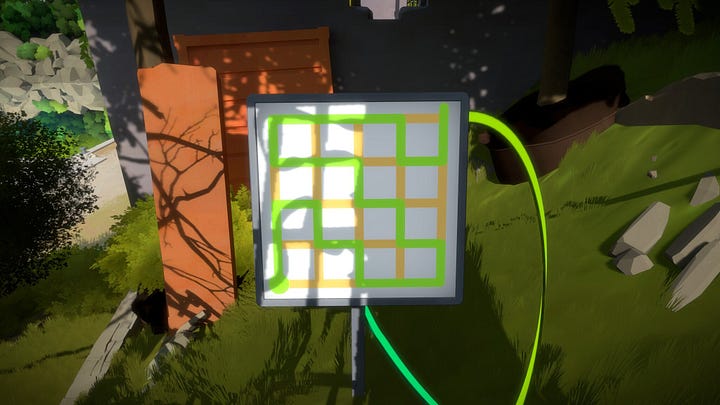

Each area features flat panels that display puzzles, generally themed to match their surroundings. Solving a puzzle panel activates one or more subsequent panels to be solved. To solve any given puzzle, you only need to rely on your wits, sight, and hearing—though this unfortunately means the game has accessibility issues for those who are colorblind or have hearing impairments. I'm certain that if the current video gaming medium could transmit touch, smell, and taste, The Witness would have utilized them as well, for reasons that will become clearer the more we go.

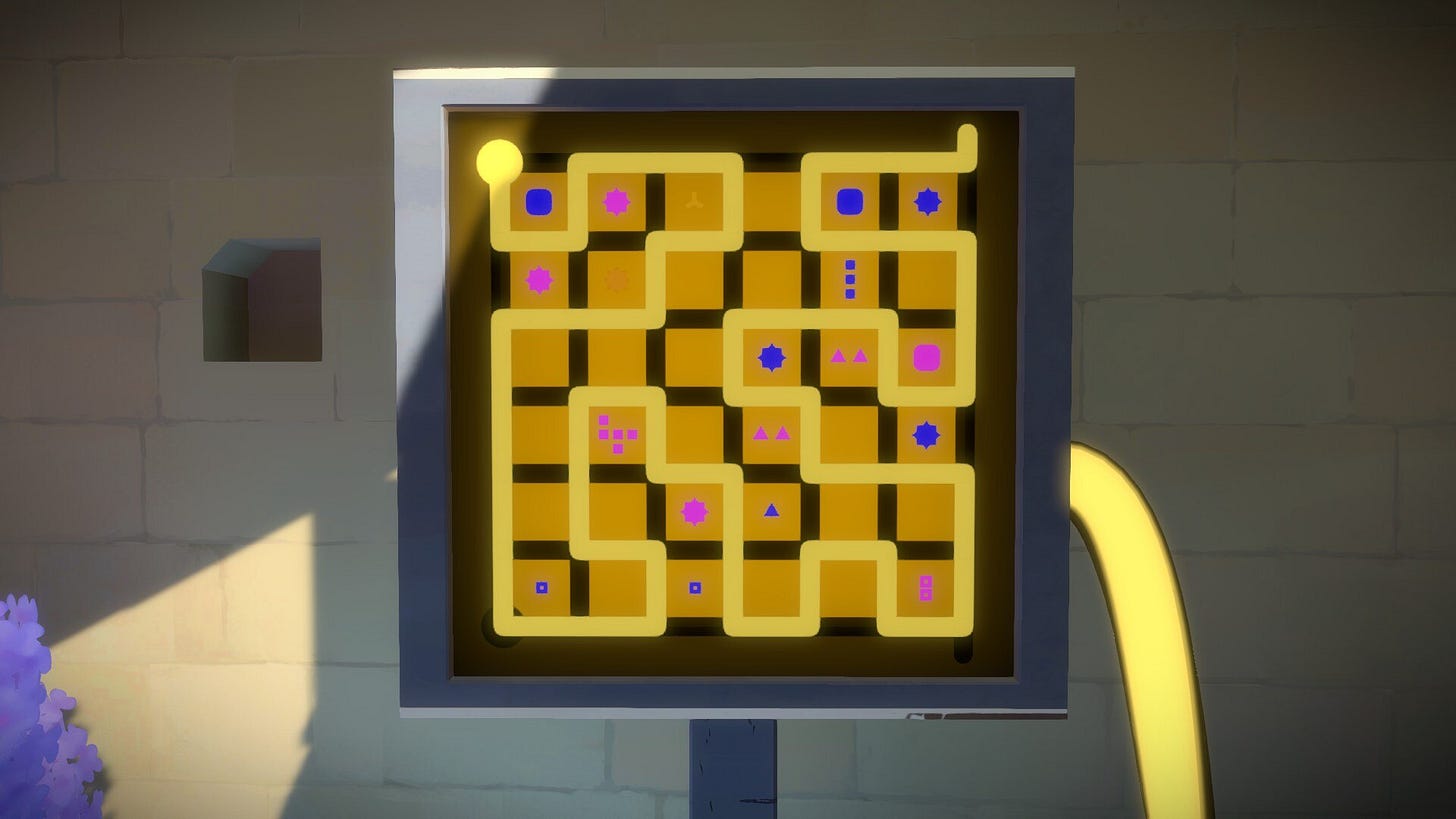

Panels can appear like these, with no rules provided in any conventional form:

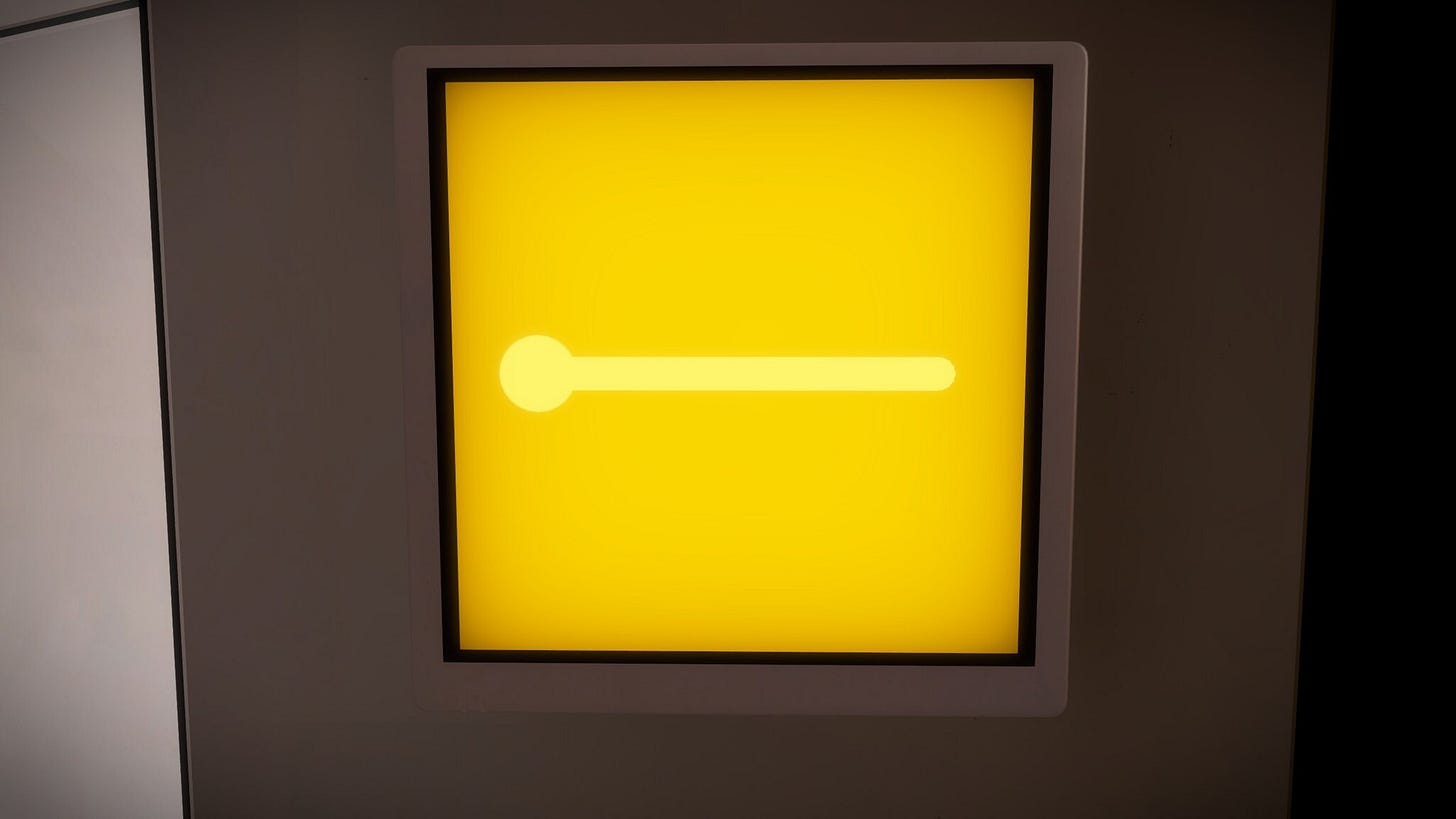

Instead of explaining the rules, the game expects you to figure them out on your own. This approach could have easily and spectacularly failed if not for the game's excellent puzzle design, which builds our understanding of the world of The Witness concept by concept, through the act of solving puzzles themselves. Here is the very first puzzle that the game presents at the very beginning:

When you try to interact with the puzzle, whether by finger, mouse, or a controller, you'll quickly discover that it has only one possible outcome, with no fail state—you simply connect the path from the starting circle to the end of the line. There is nothing else you can do with it. This becomes the foundational rule, or axiom, for all the puzzles that follow: connect the circle to the endpoint by drawing a path. Brilliant! From there, subsequent panels are introduced that very subtly build new rules on top of this initial concept.

To solve any given puzzle, all that is required is to have solved the previous puzzles, which recursively traces back to the very first puzzle—the axiom of the rules. As you progress, you discover that puzzles introduce additional nuances to these rules, either by solving them or failing to solve them. The puzzles can become quite complex, incorporating various aspects of the physical surroundings and even the properties of the panels themselves. Some puzzles cleverly use reflection and shadows cast on the panels to aid in solving them, the diegetic sound you hear or color theory. The satisfaction comes from realizing that each solved puzzle feels like a mathematical proof you’ve derived yourself, understanding and building this comprehension bit by bit, from trivial to moderate to complex.

There is indeed no narrative in The Witness. While it would be entirely understandable if the game consisted solely of puzzle panels—after all, Sudoku doesn’t require a narrative thread—the desolate island is rich with diverse architecture, statues of people, a windmill, a monastery, underground passages, a sun shrine, and other deliberately placed elements. This prompts the question: so what is this game about?

For me, the revelation came while exploring the tropical forest area, and this is a major spoiler for the game. As I was simply moving the mouse around to admire the scenery, I looked up at the sky and suddenly noticed something remarkable: from the exact spot where I was standing in-game and looking upwards, the negative space created by the trees in the forest formed the shape of a puzzle! Hesitantly, I moved the mouse towards this negative space, dragged the pointer across it, and voilà—it was indeed a puzzle.

"Oh, okay, the entire world here is the puzzle"

Immediately, I began searching for other similar puzzles, and a whole new world opened up before me. These were the same types of puzzles, created by the environment itself when viewed from the correct perspective—puzzles formed by rocks, clouds, the sun, walls, shadows, light, the river, and more. Soon, I began examining every aspect of this world with an inquisitive eye, trying to... understand it. Observant players will also notice that the pond in the middle of the island has its own purpose and reveals something about the game. All of these elements can be easily missed if you're not attentive enough.

So, The Witness is a game about understanding the world around you. It’s about the process of building this understanding step by step with our Ancient Reptilian Brain, starting from simple concepts and constructing increasingly abstract ideas. As you see the world through this progressively crafted Self, you find meaning and beauty in it.

Shortly before playing The Witness, I was an undergraduate taking a class that became my absolute favorite: Spatial and Quantitative Reasoning. Part of the class involved studying the first few books of Euclid's Elements. I'm sure this contributed to my enjoyment of the game in a big way.

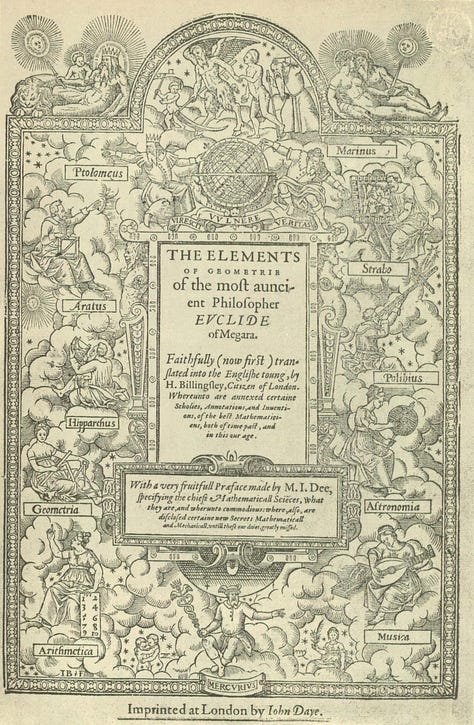

Euclid's Elements is a comprehensive deductive exploration of mathematics, covering Euclidean geometry, number theory, and incommensurable lines. This book has been instrumental in developing logic and served as a quintessential textbook for students until the 20th century, when its contents were assimilated into various other textbooks and it ceased to be considered mandatory. The work consists of mathematical definitions, postulates, and propositions, along with their corresponding proofs. Similar to The Witness, Euclid's Elements invites you to build an understanding from the simplest postulates, gradually expanding into a wealth of knowledge and higher abstractions. Here are some of the 23 definitions presented in Book I:

Definition 1: A point is that which has no part.

Definition 2: A line is breadthless length.

Definition 3: The ends of a line are points.

Definition 4: A straight line is a line which lies evenly with the points on itself.

...

Definition 15: A circle is a plane figure contained by one line such that all the straight lines falling upon it from one point among those lying within the figure equal one another.

Definition 20: Of trilateral figures, an equilateral triangle is that which has its three sides equal, an isosceles triangle that which has two of its sides alone equal, and a scalene triangle that which has its three sides unequal.

...And here are all the five postulates:

1. A straight line segment can be drawn joining any two points.

2. Any straight line segment can be extended indefinitely in a straight line.

3. Given any straight lines segment, a circle can be drawn having the segment as radius and one endpoint as center.

4. All Right Angles are congruent.

5. If two lines are drawn which intersect a third in such a way that the sum of the inner angles on one side is less than two Right Angles, then the two lines inevitably must intersect each other on that side if extended far enough. This postulate is equivalent to what is known as the Parallel Postulate.From these 5 postulates and 23 definitions, Euclid's Elements Book I provides propositions that can be proved using these postulates or by building on previously proved propositions. These propositions cover a range of topics, from constructing an equilateral triangle on a given finite straight line and bisecting an angle, to proving the equality of two parallelograms, and much much more.

As an example, here’s the first real "puzzle" from Euclid's Elements:

Proposition 1: To construct an equilateral triangle on a given finite straight line (AB). Using Postulates 1 and 3, along with Definitions 15 and 20, we can construct the triangle by following these steps:

Draw two circles, D and E, each with radius AB, centered at points A and B, respectively.

The circles will intersect at point C.

Connect points C to A and B.

To prove that the resulting triangle is equilateral, we use the fact that the radii of the circles are equal to the sides of the triangle, and hence, all three sides (AC, BC, and AB) are equal.

Triangle ABC is equilateral, as it has been constructed on the given finite straight line AB. The circles D and E, centered at A and B respectively, both have the same radius (AB). Therefore, the lengths AB, AC, and BC are all equal, confirming that triangle ABC is equilateral. So simple, so elegant.

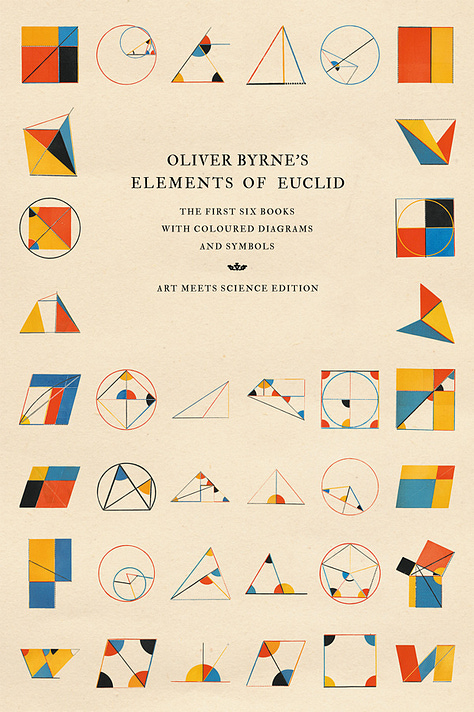

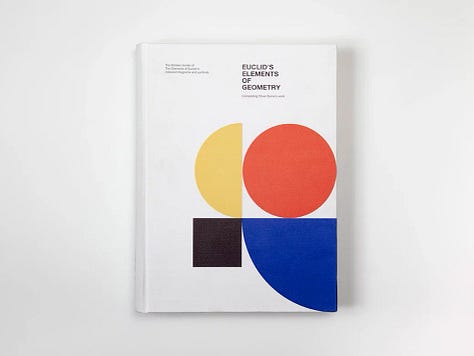

I would say The Witness is a perfect video game for those who appreciate Euclid's Elements, and vice versa. If you decide to delve into this book, I recommend starting with the generally available version. If you're feeling adventurous, consider exploring Oliver Byrne's 1847 edition, which uses color to convey mathematical properties and may be more suitable for those who think visually rather than preferring traditional mathematical notations. For those willing to spend around 200 euros, Euclid’s Elements: Completing Oliver Byrne’s Work is also available which, as the title suggests, covers more books than Byrne's edition. It’s no wonder The Witness excels in its puzzle mechanics without providing explicit instructions; it follows in the footsteps of one of the greatest works in logic.

Today, we live in a world where we must place our faith in proofs of widely established abstractions to navigate life. We must trust that wind results from pressure differences, that gravity keeps us grounded, and that non-ionizing radiation from wireless technologies doesn’t cause cancer—because few have the luxury of time to deduce these truths from the simplest postulates themselves. In fact, is it even feasible to go all the way deep? If you reeeeeally think about it, no one has ever directly observed the fundamental matter, and we are still in pursuit of a theory of everything.

This is why games like The Witness and works like Euclid's Elements offer a profound sense of satisfaction. Within the framework of their worlds—whether it’s the island in The Witness or the realm of Euclidean geometry—you can actually prove everything. Perhaps this sense of satisfaction can then inspire you to investigate the real world yourself, even if the postulates you rely on are abstract and taken for granted. As I mentioned in my overview of Disco Elysium, accepting reality as fundamentally incomplete is a crucial step in keeping your sanity.

There’s something more in the world of The Witness that I hadn’t noted until now. There are few exceptionally challenging or let's say, large-scale puzzle panels on the island which reward the player with... video clips. These include a lecture by Richard Feynman, a scene from Tarkovsky's Nostalghia (1983), James Burke discussing micro and macrocosm on BBC, and few others. However, one video clip holds a special place for me: a meditation on nonduality by Rupert Spira.

Initially, I found the other video clips straightforward to understand, but this one was different. The clip begins with the phrase "be knowingly open, empty, luminous presence of awareness." Uhm what is this guy talking about, I listened to the entire around 40 minutes of the recording, all of it felt way too abstract and highfalutin and afterwards I continued through my day. Yet somehow these words resonated in me, they lingered - "presence of awareness".

I later discovered (googled) that nonduality is essentially another name for Advaita Vedanta (or more specifically, a superset of it), a Hindu philosophical and spiritual tradition that has inspired some of my favorite works, such as The Matrix and The Big Lebowski and indirectly via TM - Twin Peaks: The Return. I went back to listen to the recording more attentively, trying to internalize the content rather than merely understanding it. It was a profound experience, leading me to a nondual understanding of the world. This perspective posits just one axiom: "I am." Everything else is built upon this personal, intimate experience and derives concepts like love, happiness and suffering from it.

This new lens has provided me with a view of the world infused with love and compassion. We are the presence of awareness; we "witness" events unfolding around us indiscriminately, and we are luminous as our consciousness renders things knowable, much like sunlight hitting our retinas. I would recommend anyone to watch this recording and meditate on it.

P.S. I can’t finish this essay without acknowledging the elephant in the room. Jonathan Blow, the talented author of The Witness, has been exhibiting a major "divorced dad" energy in recent years, and his largely center-to-right-wing political views often lack compassion and reason—an irony given the game he created. Despite this, I’ve managed to separate the art from the artist in this rare instance. I am deeply grateful for the existence of this video game and its profound influence on me. So there's that.