Gaming with OCD

Where do I even begin? This question preempts my every endeavor. The quest to perfectly project my thoughts one-to-one in a single step, without mistakes, is exhausting and unproductive. I know this, yet it’s irresistible. It’s as if I want to perform a BSOD memory dump in an instant, constructing the thought without a beginning or an end, much like how the Heptapods use their logogram writing language in the movie Arrival (2016), where sentences have no beginning or end—they come into existence in one atomic operation. I wish I could do that; I wish I could speak in a Universal Language. But, alas, I will have to concede and instead face my OCD head-on.

I didn’t have a good gaming PC growing up, nor did I have a console. I always had to play either older games or run newer ones on potato graphics settings just to try and enjoy them to some degree. Perhaps that’s why I tend to almost never play video games upon their release—I wasn’t used to it, and my PC couldn’t handle it, so the sense of immediacy is mostly (Death Stranding 2, ahem) absent. I remember when I upgraded the GPU on my PC, I immediately got a few games to test it out. These were: Prince of Persia (2008), Mirror’s Edge, Crysis, Dead Space, Assassin’s Creed, and Mass Effect—yeah, “those were the years.” However, only two from this list are more relevant in the context of this writing than the others.

It might have been the beginning of 2010; I was 16 at the time. I had just beaten the first Assassin’s Creed. I liked the Animus gimmick, the art direction, and the world-building, so I immediately proceeded to play its sequel, Assassin’s Creed II, which was already out by then. Oh boy, did I enjoy Assassin’s Creed II. It was quite an experience, but I don’t want to replay it at all, fearing that Ezio’s antics may not have aged particularly well. I enjoyed it so much that I wanted to exhaust it—I wanted to consume it fully, to feel like there was nothing left the game could offer me before I moved on. And to my delight, there were plenty of optional quests and collectibles. I completed all the achievements, which was fulfilling, and I even did all the copy-pasted assassination missions that, in retrospect, offered nothing new for the time I invested.

The same scenario played out with Mass Effect and its sequel, Mass Effect 2, which was also released by then. I did multiple playthroughs, completed all the side quests, and tried to get the “best” possible outcomes. I aimed to exhaust it entirely, ensuring I missed nothing from the experience. This behavior of “100%”-ing video games continued for a while, and, in fact, extended well beyond video games and computers in various forms, but I won’t delve into that here. I’ll stick to discussing it in the context of gaming.

Assassin’s Creed IV: Black Flag tested the limits of my compulsions. The game was open-world and packed with collectibles and missions. It might have even been my first big open-world game. During my playthrough, I realized that open-world games, which were all the hype back then, were not for me. The lack of direction, the absence of purposefully crafted scenarios, and the more sandbox-style approach of letting players craft their own stories left me unimpressed and uninspired. It felt almost lazy in terms of world design—just a terrain that told hardly any story (and I don’t mean cutscenes or narration), merely a playground for exercising power fantasies.

Of course, much later, thanks to FromSoftware and Kojima Productions, I discovered that not all open-world games lack direction. It’s simply a matter of expertise from the game designers and artists to incorporate intent, purpose, and direction, even in the largest and densest open-world games. Unfortunately, this is still a rarity to this day.

But there was something else about the open-world nature that bothered me, perhaps even more than the lack of direction and environmental guidance—it was overwhelming. It gave me choice paralysis. A series of questions arose in my mind: Where do I even begin? In what order? How can I ensure I’ve covered all of the map? How can I be sure I’ve seen and done everything without a solid structure?

What made it even worse was the sheer number of collectibles in the game. There were Treasure Chests, Viewpoints, Templar Keys, Animus Fragments, Taverns, Shanties, Mayan Stelae, Art, Manuscripts, Letters in a Bottle, and Buried Chests. The map was barely legible with all the collectible icons cluttering it.

I was compelled to collect them all. I had this unrecognized urge to make the entirety of the game figuratively part of my brain—to fully consume and integrate it. While collecting Sea Shanties, I realized I didn’t care for them at all, but I couldn’t stop. I knew I couldn’t. Every time I decided to leave an item untouched, not collected, I felt this terrible sensation that I couldn’t quite name, so I gave in. And yes, I 100%-ed Black Flag.

During my playthrough, I started to recognize a lot of things I no longer appreciate in video games: repetitive missions that differ only slightly, quest structures that bounce you between NPCs just to give the illusion of significance but, in reality, only waste time. And the map—cluttered with icons signaling the “chores” that need to be completed or collected.

After Black Flag, I decided I would only play video games that respected my time. I became very selective. Games that padded their length to hit some arbitrary “60-hour content” mark were a no-go for me. By then, I knew I would spend all that time, and if I did, I wanted it to be meaningful in every moment. Five hours of excellent playtime became far more valuable than a 30–40 hour game filled with filler content. This constraint filtered out plenty of games, but, needless to say, the core issue remained.

Even if I didn’t enjoy certain parts of a game, memorable or not, I would still force myself to finish it. Worse yet, sometimes I didn’t even enjoy the game as a whole, but I still felt compelled to complete it. Abandoning a game midway felt like an incomprehensible loss to me. It sucked. I was slowly losing the joy in my favorite pastime.

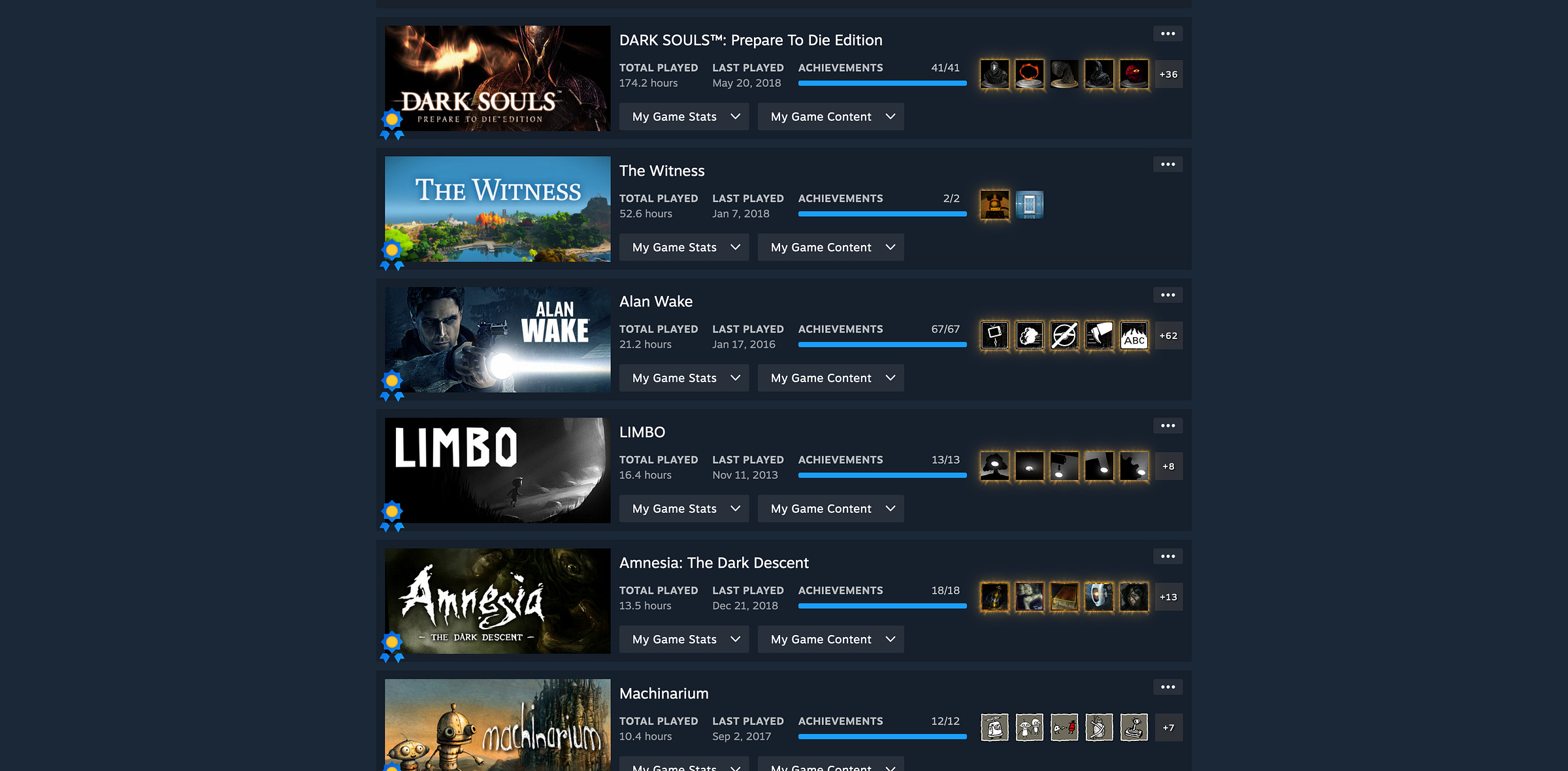

This went on for years, affecting the number of video games I played, as I spent so much time obsessively completing each one with varying degrees of enjoyment. I had already played Dark Souls, and it instantly became one of my quintessential games. I got all the achievements—this time with genuine pleasure—read everything about it, and analyzed as much as I possibly could. Then, one day, I was watching my buddy play it next to me. He was sprinting across the invisible walkways toward Seath the Scaleless, and he chose a path I hadn’t noticed before.

It was a shock—I had missed something about this game. There was knowledge I didn’t have. I was filled with sadness. I thought I had completely exhausted the game, but I hadn’t. That small, seemingly insignificant detail had escaped me. That’s when I realized that what was supposed to be an enjoyable hobby had turned into a chore, a responsibility.

I disengaged from gaming for a while—years, in fact. I observed all the exciting new games coming out, but I couldn’t bring myself to touch them. I knew I’d ruin them for myself and end up hating every second. By that time, when I was around 18 or 19, I had come to realize I had OCD, although it was yet undiagnosed. I wasn’t doing anything about it, and it only grew worse, manifesting in every aspect of daily life. It affected my relationships, my self-development, my mental well-being, my hobbies, and my ability to enjoy things. In other words, OCD is not just being “neurospicy” or getting triggered by posts on /r/mildlyinfuriating—it’s much more severe than that.

Fast forward to 2017. I was 23, and Nintendo had just released the Switch handheld console along with The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild. I decided to give it a try, with the consolation that I knew it had no achievements or trophies. It felt like a good first step toward getting back into gaming. I thoroughly enjoyed the game and did as many things as I could out of genuine enjoyment. In fact, I didn’t collect all 900 Korok seeds (which, ironically, rewards you with a… golden poop—right call, Nintendo).

This was still just a tiny step, as my playtime in Breath of the Wild reached around 200 hours, but the absence of an achievement list—a list that would have symbolized my perceived failure—made it a bit easier. It was a small step, but the right nudge I needed. For the first time, I felt that I didn’t need to chase every achievement. From that moment on, I set artificial limits for myself: aiming for “most” of the achievements, rather than 100%.

It was hard. It felt terrible at first. Knowing I had only done, say, 80% of the achievements left me uneasy, as if I’d accomplished nothing, as if I hadn’t grown or experienced anything. But I kept going, and with each game, the feeling of frustration lessened. It took a lot of patience and time to go from “most” of the achievements to aiming for only half, which represented a much lighter burden on my compulsions and allowed me to focus on enjoying quality gaming sessions.

Many years have passed since then. I was indeed diagnosed with OCD and started a treatment regimen that included Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT). This combination of calming my mind and engaging in introspection had a profound effect on me. I now understood why I had the compulsion to exhaust every possible experience in a video game. It stemmed from my drive—a compulsion to perfect myself and fill the perceived imperfections and brokenness inside me by acquiring perfect facsimiles of experiences and integrating them into my identity. As for the “why,” that’s a personal matter.

However, recognizing this endeavor as futile and truly feeling that all of it is simply impossible has been an important step for me.

As a result of all this, I now hardly pay attention to achievements or trophies. I tend to just play the game and allow myself to get lost in it—to a degree. I’m not There yet! Some things still intimidate me, especially open and expansive worlds. This is probably the main reason I have yet to start Elden Ring; I’m afraid it will suck me in, compelling me to spend hundreds of hours on it. Overcoming that will be my important step two.

Please, if you are reading this and think you might have OCD, try to get professional help. It works; it is indeed manageable. If you’d like to share your experience, feel free to contact me.